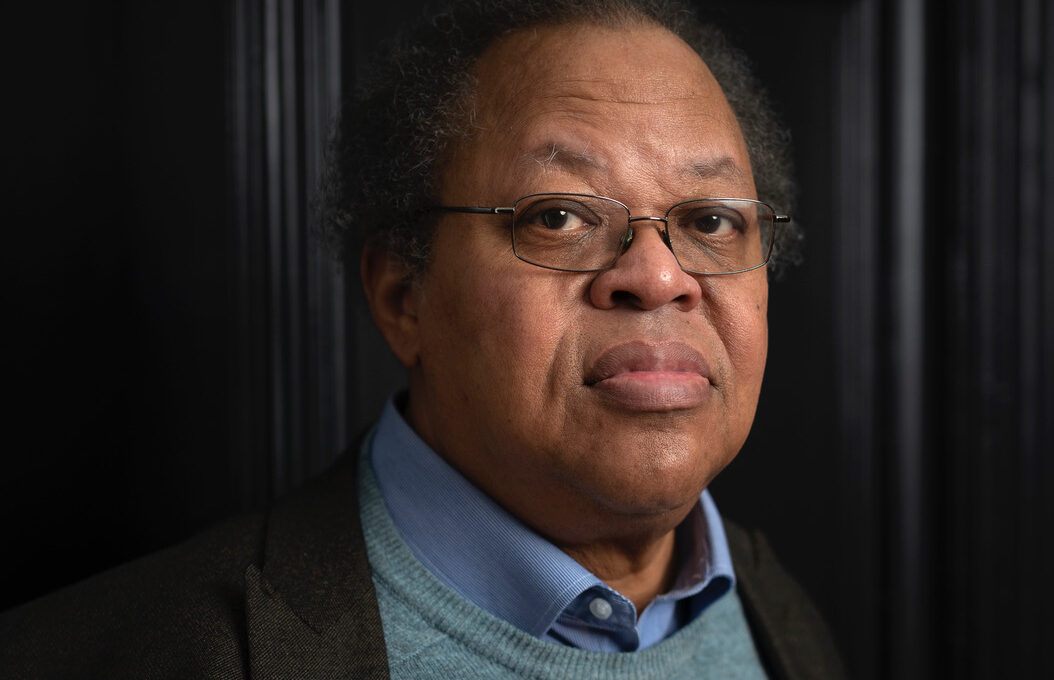

George Lewis, Professor of Music at Columbia University, is an American composer, musicologist and trombonist. He is a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, as well as a member of the Akademie der Künste Berlin.

Further honors include the Doris Duke Artist Award, a MacArthur Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He is the author of A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (University of Chicago Press), and is regarded as a pioneer in the creation of improvising computer programs. Lewis holds honorary doctorates from the University of Edinburgh, Harvard University, and the University of Pennsylvania, among others.

George Lewis is part of this years Winter Music—Echoes of Tomorrow at the Akademie der Künste on 7+8.12.2024.

FACTS

1. There is such a thing as partial truth

2. There is such a thing as partial truth

3. Afrodiasporic composers are always, already there

1. What is the biggest inspiration for your music?

I don’t think about inspiration–too romantic for me. In any event, as they used to say, creative work is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. So you don’t really need to wait for or depend on being inspired. If I did that, nothing useful would happen.

2. How and when did you get into making music?

I took part in grade school bands as a trombonist. That started in 1960 in Chicago. After that, meeting Muhal Richard Abrams and the members of the AACM in 1972 was crucial to finding out what making music was really all about, and how to be endlessly curious.

3. What are 5 of your favourite albums of all time?

Not albums, but compositions and performances

Louis Andriessen, De Tijd

John Coltrane, Naima (version on “Live at the Village Vanguard Again”, Impulse, 1966)

Franck Bedrosssian, Charleston

Richard Wagner, Parsifal

Anthony Davis, Amistad

4. What do you associate with Berlin?

* The Wall.

* The GDR musicians I played with–Conny and Hannes Bauer, Baby Sommer, Helmut Joe Sachse, Luten Petrowsky.

* Playing with Duck and Cover at the Berliner Ensemble in 1984

5. What’s your favourite place in your town?

Grunewald–like a park in a city, with swans and lakes.

6. If there was no music in the world, what would you do instead?

I’m pretty sure I’d think of something. That’s what I do—think up stuff to work on.

7. What was the last record/music you bought or listen?

JID – Kody Blu 31

8. Who would you most like to collaborate with?

I’m quite old now and have collaborated with so many people already, so collaboration is not aspirational for me. If I want to collaborate with someone I just ask them. Quite often they say yes. I’ve been fortunate in that regard.

9. What was your best gig (as performer or spectator)?

The week I spent in 2007 with the Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra taught me a great deal about the power of music to bring people together.

10. How important is technology to your creative process?

I’ve been doing AI-based music for 45 years now, so I guess *digital* technology has been pretty important to me over the decades. But I do make a lot of pieces with hands-and-breath-based technologies.

Please tell us what we can expect from your work for the Winter Music Festival?

While I was composing this work (String Quartet 4.5 “Partial Truth”) for the incredible JACK Quartet, I took some time out to attend a panel discussion with the theoretical physicist and saxophonist Stephon Alexander. During the discussion I had a chance to renew my query to him about the notion of choice in everyday life. For me, the fact that one cannot substantiate its causality renders choice as beyond the provably rational, a phenomenon that I often compare with the theory of wave-function collapse in quantum mechanics. At this point Prof Alexander, far from finding my query naïve (up to a point, that is), introduced the notion of “partial truth.” This led me to the work of Nelson C.A. Da Costa and Steven French on “partial structures, pragmatic “representations of the world that are not perfect copies but are, in certain respects, incomplete and partial.” As a humanistic scholar I was used to an analogous notion, but was not really aware of its uses in the sciences. So while I am tempted to claim that I was guided by the notion of partial structures in composing the quartet, I have to say that after hearing the premiere by JACK, I was reminded that the only real constants I was in dialogue with were relentlessness, rupture, and what African American literary theorist Houston A. Baker calls “deformation of mastery.” One apotheosis of this triumvirate of affect is to be found in the work of John Coltrane’s last living year, from 1966 to his untimely passing in July 1967. Indeed, this quartet could have been the output of a neural network trained on “Meditations/Leo.”